When carelessness, forgetfulness and coincidence become the researcher’s best friend

Who would have imagined a century ago that the annoying moulds that ruined people’s food stock held the key to curing infections? Or that an experiment with uric acid would lead to the discovery of a new treatment against bipolar disorder, although not with uric acid, but with lithium? Or that a heart medicine would provoke a completely unexpected “resurrection” that lay well outside the cardiological field?

Such unexpected and successful discoveries are examples of so-called serendipity. There are different definitions of the term, but one of them is “to discover valuable and beneficial findings you were not looking for”.

The word originates from an ancient Persian tale, “The Three Princes of Serendib” (ancient Persian name for Sri Lanka). The heroes of Serendib travelled and, by pure chance and thanks to their acumen, continually discovered fantastic new things and phenomena they were not in any way looking for.

The discoveries of Archimedes and Columbus are two obvious examples, but there are also many examples in the medical field, some of which are famous, others not so well known, and we describe some of them in this article.

However, to call pioneering scientific advances attributable to serendipity pure luck is wrong, as it requires great knowledge and a flexible intellect to identify successful coincidences and understand their significance.

Or as Louis Pasteur said: “La chance ne sourit qu'aux esprits bien préparé” ‒ Happiness only smiles at minds that are well prepared.

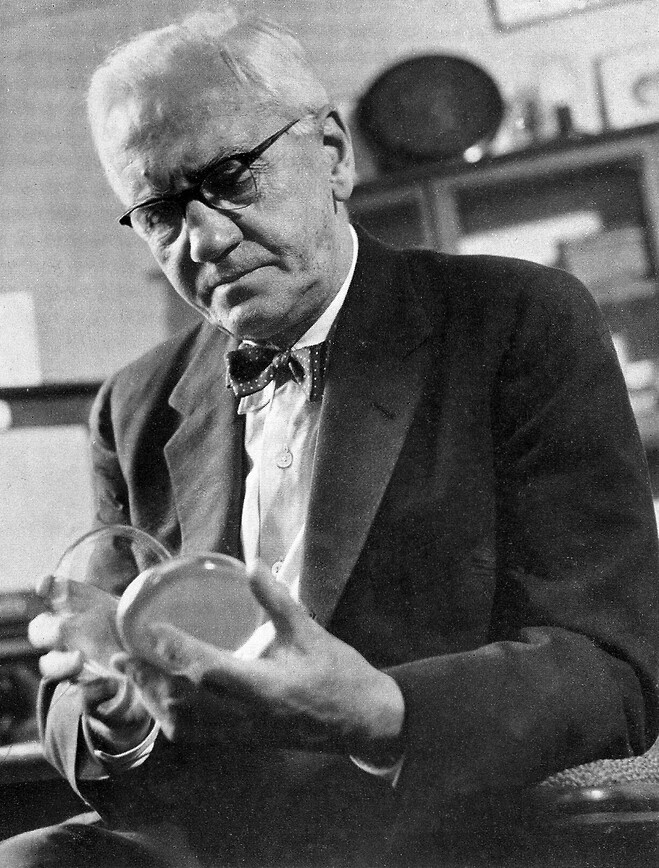

Alexander Fleming and penicillin

In August 1928, the then 47-year-old bacteriologist Alexander Fleming went on a well-deserved holiday from his work at St. Mary’s Hospital in London. At the time, he was doing research on staphylococci, which he grew in Petri dishes, and he happened to leave one of them on a desk in his lab.

On his return two weeks later, he found the dish and also discovered a mould stain next to the edge of the dish, whose lid apparently was not properly sealed.

He also found that the bacteria closest to the mould had died.

Fleming’s curiosity was aroused and he examined the mould that turned out to be Penicillium notatum, and the rest is history. In 1945, Alexander Fleming was awarded the Nobel Prize “for discovering penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases”.

Inefficient against angina but it still became a historic blockbuster

When Pfizer developed the drug sildenafil, the idea was to find a treatment against high blood pressure and angina, but the early tests in the early 1990s were disappointing ‒ for those hoping for a new heart medicine.

However, the compound had some unexpected and obvious side effects. Many of the 3,000 men between the ages of 19 and 87 participating in the clinical trials reported prolonged erections, and those who suffered from impotence problems experienced very concrete improvements.

Sildenafil did not become a heart medicine, but in 1998 the drug was approved as a treatment for erectile dysfunction (impotence) under the name Viagra.

Researchers in Uppsala discovered Upsalite

In 2013, coincidence ‒ or rather oblivion ‒ helped researchers at the Ångström Laboratory at Uppsala University to produce a nanomaterial with astonishing properties.

For some time, researchers had unsuccessfully tried to produce magnesium carbonate. However, something happened when they changed the synthesis process and accidentally left the compound over the weekend.

When the researchers returned on Monday morning, a gel had formed in the vessel, and when analysing the dried gel, the researchers got increasingly excited. After analyses, Maria Strømme, Professor of Nanotechnology and Research Manager, could establish that she and her colleagues had produced magnesium carbonate in a previously thought impossible way.

The material, which was named Upsalite, turned out to have greater water adsorption than any other then known material, and among other things, it has proved able to effectively increase the solubility of several insoluble drugs.

What calmed the guinea pigs?

In the 1940s, Australian psychiatrist John Cade searched for an explanation for mania, depression and bipolar disorder. Through rather macabre experiments on guinea pigs, he came to the conclusion that uric acid from manic patients was more harmful than other uric acid and thought he was on to something.

Now he needed detailed tests of the effect of uric acid, and to make it more water-soluble, he added lithium carbonate. The effect was not as expected, as the guinea pigs instead seemed to be protected from the adverse effects of uric acid. They were strangely calmed and lay down quietly on their backs instead of running around. Could it be an effect of the lithium?

In clinical trials, John Cade was soon able to show that the metal brought about dramatic improvement in patients with bipolar disorder. Even today, lithium is used to treat mania and depression, and it is still the most common treatment for bipolar disorder.

World discovery ‒ in rabbit bones

In the early 1950s, the young researcher Per-Ingvar Brånemark (1929-2014) investigated how the blood supply affects healing in bone tissue. To conduct the study, small titanium observation chambers were surgically inserted into the bones of rabbits.

At the end of the experiment, it was time to remove the titanium chambers, but then a surprise awaited. The bone tissue had grown and stuck to the titanium, in contrast to how bone tissue usually reacts to metal objects.

Brånemark quickly realised the significance of the discovery, and he became one of the pioneers in osseointegration, which aims to create a stable transition between titanium implants and bones. The method is strongly associated with dental implants, where a ceramic denture is attached directly to the jawbone with a titanium screw. Titanium implants also have many other applications, such as boneanchored hearing aids and implants in plastic surgery and orthopaedics.

Artikeln är en del av vårt tema om News in English.

Av

Av